“I have a BRCA mutation and haven’t had cancer. I’m taking tamoxifen preventively – hoping to reduce my risk of getting breast cancer – and it isn’t horrible.”

Those two sentences are true for me as I write them today. Four months ago, when I was trying to decide whether or not to go a on a five-year course of tamoxifen, I would have loved to read or hear something along those lines. Now, I hope that my experience with chemoprevention and tamoxifen might be useful for some other woman out there wrestling with the same question.

Obviously, my experience is only that – mine. Each BRCA+ woman has her own constellation of health status, emotional considerations, and preferences that will all feed into her decisions about preventive and screening measures. I am not recommending tamoxifen for anybody else. But for me it was a good choice, one I’m glad I made. And despite all my fears, so far I feel fine. Good, even.

I was very hesitant about – no, let’s be honest, I was scared about – taking this medication. And I could find very little first person experience from women like me, as opposed to those taking tamoxifen as part of their cancer treatment. And what I read or heard about tamoxifen from the latter group made me very nervous. Okay, afraid.

But for me, it has been okay. I don’t feel terrible on tamoxifen. And I do believe I am helping reduce the chance that I will one day get breast cancer. There is no guarantee, certainly, but for me it was a good decision.

Three and a half years ago, when I was first identified as BRCA+, the genetic experts I consulted with brought up the possibility of chemoprevention with tamoxifen. But they didn’t argue for it strongly and I had other more pressing issues to deal with at the time: scheduling surgery to remove my ovaries and fallopian tubes, which meant premature menopause was coming, plus deciding whether to do prophylactic mastectomies or (my ultimate decision) high risk, enhanced breast screening (MRI and mammogram/ ultrasound).

The paperwork from those initial medical visits mentions the potential use of tamoxifen, but I set the question aside for then. I needed to triage.

Nearly three years later, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force came out with new recommendations supporting the potential use of tamoxifen and similar drugs for reducing the risk of breast cancer in high-risk women.

http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf13/breastcanmeds/breastcanmedsrs.htm

It was covered in the media (see http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/16/health/breast-cancer-drugs-urged-for-healthy-high-risk-women.html?ref=preventiveservicestaskforce) as well as in breast cancer blogs and facebook groups, etc. So I couldn’t help but again confront the question – should I take tamoxifen?

Now fear comes back into the story. I did a little research and found a lot of information about women having bad experiences with tamoxifen – hot flashes and vaginal dryness, to start – plus a daunting list of serious potential side effects, including an elevated risk of blood clots, strokes, cataracts and endometrial cancer.

I was worried about all that, but those new recommendations left me wanting to at least explore the question. So I made an appointment to talk with Dr. K, the one with expertise in managing high risk patients. I was shaky when I hung up the phone after talking with the scheduler. But I was just going to talk to Dr. K. I wasn’t committing to take any action beyond that.

Fast forward to the appointment. I didn’t cancel it, though I’d considered doing so, several times.

Dr. K was pretty clear. For me, the potential benefits of tamoxifen outweighed the risks. She recommended that I do it.

It is a very individual matter, weighing the costs and benefits, both objectively as far as the patient’s particular health issues and also subjectively as far as the patient’s comfort with the medication. Obviously, if you are wondering about your particular situation you will need to consult with a physician. It is a balancing act. My balance wouldn’t necessarily be the same as yours.

On the benefit side of the coin for me, with a BRCA2 mutation I’m at high risk for breast cancer (45% or more) and a five-year course of tamoxifen might reduce that risk by 1/3 to ½. That was substantial. And the risk side was relatively low, given my good health otherwise and my lack of significant risk factors for the various serious health problems which tamoxifen can make more likely.

With respect to experiential side effects – the dreaded hot flashes, etc. – Dr. K assured me there were ways to counteract those issues if I experienced them. And if I really hated how I felt, I could just stop taking it. I had an escape plan, if needed.

I couldn’t decide, either way, during that appointment. So I didn’t. I went home to think about it. I was very hesitant (okay, afraid) and that was fine. I had time to learn more, to think and decide. I spent a couple of weeks doing more research, pondering, and directing questions to Dr. K by hone or email.

Eventually I decided to do it.

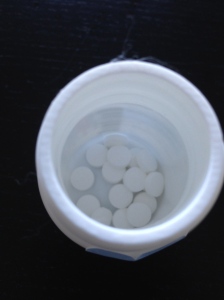

I called my doctor and got the prescription. I would take 1 pill daily, at the same time each day, for five years. Presuming I didn’t use the escape plan.

Prescription filled, I read all the associated paperwork, the lengthy package inserts detailing the potential side effects and counter-indications. Those lists can be extensive for even the most innocuous drug. For tamoxifen it was rather overwhelming, but I forged through.

And then I didn’t start taking my daily tamoxifen pill for nearly a week. Intellectually I thought I was ready, but seemingly not enough to take actually the plunge.

Until one day I just was. I had processed the decision in the way that I needed to, I guess. And after all the concern and the fear, it has been fine. I noticed an increase in hot flashes, early on, but since then things have settled down. I feel just about the same as I did before.

Except maybe a bit more hopeful – that every tamoxifen pill I take may be helping to reduce my breast cancer risk…